GOSPEL OF THOMAS INTERPRETED and EXPLAINED

The Gospel of Thomas is fully interpreted and explained through the book, 77th Pearl: the Perpetual Tree, and this website. The Gospel of Thomas was discovered in 1945 at a place called Nag Hammadi, in Upper Egypt. It is one of the most controversial texts associated with the person known as Jesus (Yeshua). Through the canonical texts, Christians maintain that faith is all one needs to attain eternal life – the Gospel of Thomas teaches us that wisdom is the key. This gospel tells us that Yeshua gave one disciple His secret teachings, knowledge the other disciples could not accept or understand. The Gospel of Thomas was so dangerous to the fledgling Christian community that it was categorised as Gnostic and heretical. In 77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree we discover something astonishing. Here, the Gospel of Thomas is interpreted and explained through a careful analysis of all the sayings and how they relate.

In December 2017, the New York Times ran a story, Glowing Auras and ‘Black Money’: The Pentagon’s Mysterious UFO Program. The article shook the world. It confirmed that military personnel, in 2004, had reported several encounters with UAP (Unidentified Aerial Phenomena). In June 2021, the Pentagon released a report, Preliminary Assessment: Unidentified Aerial Phenomena, which confirmed that there were indeed significant incidents of UAP incursions into military and commercial airspace. Significantly, the report suggested that these objects should be reported and researched.

These revelations confirmed what many ufologists had been reporting for the past seventy years. Moreover, professionals such as Dr John Mack (psychiatrist) and Dr Jacques Vallee (scientist) had concluded that these encounters are not just physical. For many people they have a psychological impact, which changes the individual’s world view and perceptions of reality. Researchers are now suggesting that consciousness is the key to understanding this phenomena.

The conclusions of contemporary UAP researchers ratify the teachings we find in the Gospel of Thomas, which is interpreted and explained in 77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree. This material dimension is just another layer of many, which human beings are just starting to explore. Theories about quantum physics and the nature of the universe are bringing us closer to the wisdom already revealed to humanity by a Light being called Yeshua.

If the Gospel of Thomas interpretation and explanation you have found here resonates with you, please share this website with others. Below you will find a link to a YouTube channel which has audio extracts from the book. The audiobook can be downloaded from Google Play or your preferred supplier. You may download the free ePub from the dropdown menu above. The hardcover is available from Amazon (link below) or your preferred supplier.

I bow to the divine in you.

GOSPEL OF THOMAS

77th PEARL: THE PERPETUAL TREE

The Gospel of Thomas advocates a deep personal connection to God (Source) through the understanding that we are one.

God is in humanity. This is not a religion, this is the Gospel of Thomas and it is interpreted and explained in

77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree.

77ème Perle : L’Arbre Perpétuel est maintenant disponible en français –

cliquez sur les “RELATED LINKS” ci-dessus pour télécharger l’ebook

Perla 77: El Árbol Perpetuo está disponible en español.

Haga clic en los “RELATED LINKS” de arriba para descargar el ibook gratis.

For audio versions of the extracts found below go to the YouTube channel.

Gospel of Thomas Interpretation and Explanation

– Introduction –

Gospel of Thomas interpretation and explanation discourses have been many and varied. These texts will often use the Old Testament, New Testament and Gnostic writings to achieve their goals. This book is different. The secret teachings of Yeshua (Jesus) in the Gospel of Thomas are self-contained. To extract meaning from the cryptic sayings, one has to make crucial links between them to crack their code. For example, many people have argued that, because of the apparently misogynistic façade, Thomas 114 should not be considered part of the original version of this gospel. However, when one applies the wisdom of Thomas 22, to the controversial Thomas 114, it becomes clear what Jesus was doing with His careful choice of words. This cross-referencing of significant sayings has been the key to unlocking the secret teachings, something you will not find in other texts on the Gospel of Thomas. References to the New Testament Gospels and other relevant texts are only made to clarify the links and points within the commentaries.

Contemporary Christian faiths present salvation as either a firm belief in Jesus Christ and/or the completion of sacraments. Faith in the existence of Jesus (also referred to here as Yeshua) does not in itself bring us into a state of grace, nor does the completion of sacraments. These conclusions are logical. This kind of faith, and involvement in rituals, reflects the archaic needs and attributes of the primal human. They are behaviours that console, but they do not provide a consistent connection to the thing our soul originated from. Understanding the truth is crucial. Through this understanding comes inner peace.

In the middle of January 2015 Pope Francis visited the Philippines. On this visit, a twelve-year-old girl gave a speech and asked the Pope: ‘why does God allow children to suffer?’ This question and the girl’s tears visibly moved the Pope, but he had no real answer for the child. This illustrates the problem with the current Christian orthodoxy. God has been made into a patriarchal figurehead. A majority of Christians believe that this god makes conscious decisions about the events in their everyday lives. This is evident in the numerous times we see sportspeople, musicians, and actors receive a commendation and proceed to thank God for their talents. God does not make one person talented above another. These talents, or attributes, are acquired through good genes, hard work, and being in the right place, at the right time. We should ask ourselves: what does this kind of rhetoric and thinking do to a young person, who does not have any of these talents or opportunities? Is the god of these talented people favouring them, just as he favours children who live in a healthy, happy environment? This kind of fictitious, patriarchal god comes to us from humanity’s primal heritage, where these prehistoric groups were reliant on an alpha-male for guidance and protection. Is this the kind of father Yeshua spoke of? The answer is a resounding no. In response to the child’s question, we would point out that our world is as it is because of the way we have evolved—from a creature that is fallible. The decisions humans made have given us a world that is overpopulated and an environment that is being eroded. Most people in our world are materialistic and make decisions favouring economic growth, rather than ethical approaches to community, environment, and business affairs. Believing that a supreme godhead will solve all these issues is a false perception and a very dangerous one. It is the root cause of much of the world’s problems at the infancy of the twenty-first century. 77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree reveals a logical solution: we must understand what Yeshua truly meant in His teachings. This truth permits us to separate religion from global affairs and allows science to work with matters that relate to the material world. It means we use the logic of science to make decisions pertaining to our physical existence, which will give us a world that is free of self-imposed suffering. The world of the Spirit is completely different to the world we experience with our limited physical senses. This universe has been inspired by another realm/dimension, but it is not controlled by it. Ultimately, this is the answer to the child’s question.

Most humans see themselves living in a dualistic existence, evident in the apparent separation of soul/mind and body. This is mirrored in the compartmentalisation of religion as an activity permeated with rituals, rather than a deep, personal understanding of the self. What people should be doing is asking the question, what is consciousness and how is the mind linked to the quantum field? Since around the 1950’s, ufologists have been gathering evidence, which has seen links made between extra-terrestrial life and the human psyche. In June of 2021, the Pentagon released a report called, Preliminary Assessment: Unidentified Aerial Phenomena, which confirmed that there were indeed significant incidents of UAP incursions into military and commercial airspace. This official confirmation, together with articles about these incursions in reputable media outlets, such as the New York Times, has allowed the UFO/UAP phenomena to be taken seriously, rather than its usual relegation into the fringe, woo portion of society. It has also opened the door for a new discourse, validating the notion that current models of physics cannot explain reality as it actually stands. The Gospel of Thomas is linked to this discourse through its explanation of what the human is, beyond the physical body. In the Gospel of Thomas interpretation and explanation in this text these links become evident.

In 1945, at a place called Nag Hammadi, in Upper Egypt, an Arab peasant discovered fifty-two texts in an earthenware jar. Among those texts was the Gospel of Thomas. This gospel is set out in 114 sayings that are considered the secret sayings of Jesus. While some of these sayings appear in the New Testament Gospels, they are presented here in their unedited form. Since the time of Jesus, people have tried to comprehend the sayings, in particular, those that were omitted from the canonical gospels. In 77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree, all the sayings are explored in relation to each other and to pertinent New Testament Gospels. The sayings reveal truths, which lift the mystical teachings of Jesus into a logical reality, at times reflecting what scientists are discovering in the first phase of the twenty-first century.

The New Testament Gospels are referred to as the Synoptic Gospels, meaning that they have a common view. These Synoptic Gospels refer to the three New Testament Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke and are considered synoptic because of their similarity. With the inclusion of the fourth Gospel of John we have the canonical gospels. In 77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree, the Gospel of Mark is often referred to in comparison to Thomas, as it is known to be the first of the three Synoptic Gospels written. The other Synoptic Gospels are considered elaborations on Mark. Biblical scholars have suggested that there is another source and it becomes apparent that this is indeed the Gospel of Thomas. It is the cryptic nature of significant portions of the Gospel of Thomas that categorised it as a heretical text to the early Church authorities. Christian apologists argue that the sayings, which are not in the New Testament, are words a typical rabbi, in the time of Jesus, would not have spoken. 77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree concurs with this point of view. Yeshua was a man that had an entirely new message, a message that was ahead of its time. In the New Testament, we see the disciples of Jesus ask Him why He speaks to them in strange riddles, yet all we find in these accounts is a narrative interwoven with fantastic feats, which are supposed to prove His divinity. In the New Testament, there is nothing about these strange riddles and mysteries that explains what we are, or our deep connection to the Father/Source. These things, which they considered strange and difficult to fathom, were omitted. The cryptic sayings were meant for the twenty-first century and beyond. In a sense, these words, revealed through 77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree, are the second coming.

While the Gospel of Thomas we now know was discovered in 1945, it did in fact exist at the time of the New Testament Gospels. Bishop Irenaeus of Lyon c.180. made references to the Gospel of Thomas in scathing letters, written against the Gnostic’s who held it in high regard. Due to the texts being deemed heretical, orthodox believers sought to destroy them. This is why some prudent Gnostic’s had the foresight to hide the documents.

The popularity of atheism and agnosticism is symptomatic of how the mainstream religions do not bridge the gap between the realities of life and the belief in a deity. A deity that is supposed to provide protection and guidance. Often we see that suffering and death can happen to any individual, group, or community. Sceptics rightly ask: why does a god, who created humans, allow them to suffer from diseases and natural disasters? The Gospel of Thomas answers these perplexing questions by revealing what we are and why we are in this place. If Christian readers are sceptical towards the authenticity of the Gospel of Thomas, as compared to other texts, then they should ask themselves—is the message speaking to the soul or is it speaking from a man?

Some scholars have labelled the Gospel of Thomas a Gnostic text but 77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree does not support this premise. The Gospel of Thomas is free of Gnostic mythology; therefore, it is not from this early Christian splinter group. The Gospel of Thomas was the springboard for Gnostic Christianity, because it challenges the reader to search for the truth. Gnostics took this to mean that they were required to find hidden messages in the sayings, to unlock the various gates leading to heaven. What we discover is that the Gnostics went too far—creating numerous complex myths, which supposedly explained our predicament in this world and how to escape from it. These myths prove to be derived from observations of human characteristics and frailties, not unlike how the Ancient Greeks attributed human weaknesses to the plethora of gods they created.

77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree reveals knowledge hidden in cryptic sayings for millennia. It does not reconcile ancient beliefs rooted in the Old Testament with scientific fact. It also does not support Intelligent Design, which is negated in the saying of Thomas 97. What it does do is recognise what science has consistently proven—that we are flesh and bone. We exist in a world governed by physical laws of cause and effect, all of which are external layers of the source of all things—the one Jesus refers to as His ‘father’. In these sayings, the disparity between the physical world and the realm of the Spirit is an ongoing theme. Who created this world and why is not the primary concern. Its physical make-up and evolution has, for the most part, been proven by science and accepted by the Catholic Church. However, this leaves us with many questions. These questions are ones that antiquated faiths, rooted in myths and legends, are incapable of answering. Yeshua foresaw this when He warned that His teachings could not be placed into old wineskins (the context of the Old Testament). Yeshua was the new wine, which would be spoiled by this action.

The author discovered The Gospel of Thomas when he befriended a progressive young Catholic priest in the early 1990’s. Inquisitive conversations often took place, which centred on the contradictions in Church teachings and the Old and New Testaments. One day, rather ironically, the young priest gave the author a book called ‘The Gnostic Gospels’ by Elaine Pagels. In this text, the author found references to the ‘Gospel of Thomas’ and these first few insights opened his eyes to a truth. For the first time he felt a deep spiritual connection, for the first time he felt whole. This started the journey towards a Gospel of Thomas interpretation and explanation that was unlike any other.

A visit, in 2002, to the Vatican Basilica in Rome cemented in the author a desire to know the truth. During this visit to the Vatican he saw three altars, each presumably containing the body of a Pope. The bodies were in glass coffins, dressed in fine white robes inlaid with gold threads and jewels. The feet of the bodies were adorned with gold shoes encrusted in gems. The faces were covered in a gold mask also covered in gems. A strong smell of what seemed to be formaldehyde surrounded the coffins. As he stood in this place, which was supposed to represent the centre of Christianity, the author felt an incredible sadness and absence of Spirit. In his mind, he could see Jesus entering that space and overturning those altars in disgust at what His representatives had done in His name. This was a crucial first step toward 77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree.

The traditional relationship with the God of the Abraham lineage is lacking something essential. This relationship fails to answer the eternal question that humans have grappled with since, presumably, we came down from the trees—what is the meaning of life and what does it mean to live? The information we have had access to in the past has been tainted. The contradictions we encounter in the knowledge presented to us, through the religions sharing the Abrahamic heritage, lack logic. It is also damaging people’s potential to reconcile their human condition, as a reality, apart from the spiritual. The Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are the three-sided grain, which has entered the oyster (this realm/world) to form a pearl. The light that reflects off this pearl has made the revelations in the Gospel of Thomas shine through the fog, which are the physical barriers in this world.

Humans, who are searching for the truth, know that there is an intimate relationship shared with the source of all things—the one Jesus refers to as His father. This relationship is one that has been forgotten, primarily because people’s physical existence steals them away from the Light they cannot see. The thing that one cannot point to when we refer to the ‘self’, is the thing that shares a kinship with Jesus. Within the Gospel of Thomas interpretation and explanation, there are threads that appear which link the sayings in the gospel—a prominent one is that Jesus is our brother.

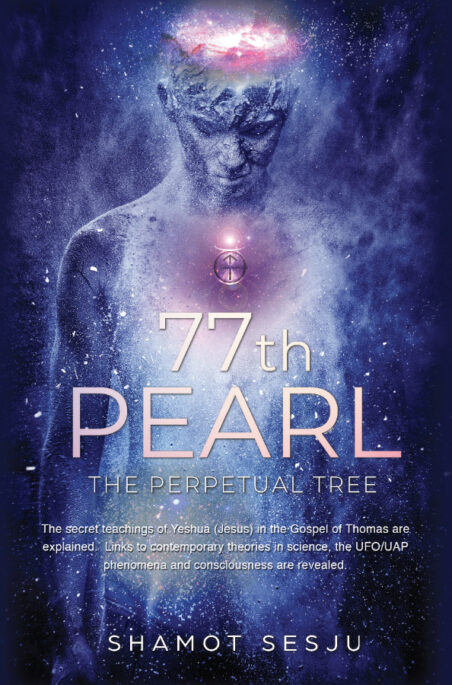

The symbol on the front of this text represents the perfect human—one that is neither male nor female and both of these at the same time. This symbol speaks of the disparity between our knowledge of relationships, based on physical manifestations, and how Yeshua really wants us to see ourselves. This thing is Spirit and it cannot be defined by the parameters of this world. The vessel on top of the symbol represents the search for knowledge and truth.

The English translation of the Gospel of Thomas used here is by Stephen Patterson and Marvin Meyer: The Nag Hammadi Library. Some of the sayings have words missing due to the fragile nature of the material they were originally written upon. In such cases the scholars have indicated missing words with “[…]” or brackets with the most likely word.

Gospel of Thomas Compared to The New Testament

Thomas 9 is a well-known and often quoted parable. For this reason, this is an appropriate place to point out that the Gospel of Thomas sayings were a reference point for the Synoptic Gospels. The authors did not understand the esoteric nature of the sayings. They used what they knew from the Old Testament edicts to substantiate theories about Jesus and His teachings. This re-contextualising is what Jesus warned should not occur when He cryptically asserted not to place new wine (His teachings) into old wine skins (the myths and legends of the Old Testament) in Thomas 47. The fact that the disciples found Jesus’ sayings difficult to comprehend is evident in the New Testament Gospels. The Gospel of Matthew illustrates this confusion well.

In Matthew 13, we see a plethora of sayings from the Gospel of Thomas. They are used to construct a piece of writing devised to scare and persuade the reader into believing in the salvation Matthew describes. This salvation would see the righteous taken up into heaven and the evil ones destroyed in the most agonising manner—such that there would be ‘weeping and grinding of teeth’. This kind of persuasive language, devised to create frightening imagery, would have had great impact on the uneducated people of the early Christian period, and, in some Churches, right up to the twenty-first century. This fear is abundant in the Abrahamic religions and it is why 77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree was required for humanity to evolve.

Matthew 13 starts with the appropriation of Thomas 9. The author of the gospel uses the parable to describe the importance of faith and how the Evil One and daily life can sway and obstruct our faith. Just prior to the explanation of the sower parable, the disciples ask Jesus why He speaks to crowds in these parables. In reply, Matthew’s Jesus says: ‘Because to you is granted to understand the mysteries of the kingdom of Heaven, but to them it is not granted.’ (Matthew 13:11) This is followed by a variation on Thomas 41, which suggests that those who have the faith (implied) will be given more; those who do not, the little they have will be taken away. This is a crafty edit of the teachings found in the Gospel of Thomas. They were not meant to sit together in this way and certainly were not to be used in such a political manner—the Son of God versus the Evil One. Moreover, suggesting that the parables were only meant to be understood by the disciples is clearly an attempt by the author to reaffirm his position and authority. At the very beginning of the Gospel of Thomas we see that this was not Jesus’ intention. These teachings were for all people, but they needed to have wanted to understand them for the doors to be opened. Ironically, the statement in Matthew 13:11 confirms that there were parables that were ‘mysteries’ in Jesus’ teachings. People found them difficult to understand; this included the disciples and the generations after Yeshua. It is only now, in the twenty-first century, that these mysteries are being revealed for the first time. In the New Testament, we generally see words about love, peace, and forgiveness, with the addition of Christology in the Gospel of John. We do not see teachings which are of an esoteric nature. Thomas understood the importance of these teachings and could not ignore them—as farmers know good, fertile soil when they see it.

In the same chapter of Matthew 13, the author uses the saying of Thomas 57, which makes reference to good and bad seed. In the synoptic text, it is used to continue the narrative of the Evil One placing obstacles in the path of Christians—obstacles that will be thrown into the furnace, where yet again: ‘there will be weeping and grinding of teeth’. A brief history of the Evil One is discussed later. That section demonstrates how people are in fact Satan, which is something the synoptic writers inadvertently revealed. Following Thomas 57, the author of Matthew 13 inserts Thomas 20 (the mustard seed) and Thomas 96 (the woman who places leaven into bread). These sayings are interpreted in a peripheral, literal sense, twisted in subtle ways to suit the author’s intention. Matthew 13 demonstrates how, through careful selection and juxtaposed narrative, the cryptic sayings in the Gospel of Thomas serve the synoptic authors’ intentions. Matthew 13 also includes Thomas 109 (the treasure hidden in the field), Thomas 76 (the merchant and the pearl), and Thomas 8 (the large fish). The inclusion of the latter is used to persuade the reader of ‘how it will be at the end of time.’ The angels will separate the wicked from the upright and there will be yet more weeping and grinding of teeth. This is not the intended meaning of Thomas 8, as we clearly see in the first line the reference is to a person who is like a wise fisherman – someone who is discerning and a critical thinker. This original meaning does not have purpose in a text intended to frighten and control the diaspora.

Toward the end of Matthew 13, we see a strong polemic statement in verse 52: ‘Well then, every scribe who becomes a disciple of the kingdom of Heaven is like a householder who brings out from his storeroom new things as well as old.’ This infers a justification for using the Gospel of Thomas sayings in the context of knowledge derived from the Old Testament and previous gospels. It also presents an argument against Thomas 47, where Yeshua tells His followers that His teachings are the new wine (the new way) and should not be placed into old wine skins. Nor can one ‘mount two horses’—that is, two belief systems, which are not of the same essential construct. We should also note that the author describes himself as a ‘disciple of the kingdom of Heaven’—not a disciple of Jesus. The author of this gospel was not the direct disciple of Jesus, nor were the authors of the other gospels.

The author ends Matthew 13 with Thomas 31. Jesus states that ‘…doctors don’t cure those who know them’, referring to a visit to His hometown, where no one was healed. Their perception of Him was that He was simply the carpenter’s son. This is another device to show the reader that faith is the subject of Matthew 13. It espouses the need to believe in Jesus as the Christ if people are to be saved. This premise illustrates the main problem with the canonical texts. They do not tackle the meaning of Jesus’ teachings. They instead use them to attempt to convince an audience of what Yeshua was—a definition the authors found in the Old Testament. This fundamental problem, placing the divine outside of the self, is what Yeshua came to this realm to correct. It is an attitude derived from humanities primal heritage, where ancient peoples looked outwardly, toward nature, for an explanation of the mysteries they could not fathom.

In the Gospel of Thomas, we are shown that we have an intimate connection with the Father—the Source of all things. Those who are seeking It are the sons, just as Yeshua is the Son, because the soul is an energy that has come from the Source and aggregates in humans. Thomas 9 tells us the seeds (the teachings) grow in ‘good soil’. When we read Thomas 9 out of its context, such as in Matthew 13, we see how Yeshua’s lament about the rocks and thorns was realised. In Matthew, the ‘seeds’ become faith, which is destroyed by external, evil forces. In Thomas 9, the ‘soil’ is the focus, because it is where the roots create growth. This is what Jesus was concerned with—growth of the soul. The fertile soil is knowledge, which allows growth.

Jesus (Yeshua) and Buddha – Thomas 7

In 77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree, we find strong links made between Gautama Buddha and Jesus of Nazareth. They are logical links, made through the teachings in the Gospel of Thomas and the central teaching established through Paticcasamuppada. Here, a distinction is drawn between Buddhist teachings in the original Pali Canon and the popularised Sanskrit version of Buddhism. This distinction is similar to the difference we find between the Christian orthodoxy (denominations that only accept canonical Bible doctrine) and the teachings found in the Gospel of Thomas.

Two related topics and authors are mentioned here. They describe knowledge and understanding that is crucial in appreciating the links between Jesus of Nazareth and Gautama Buddha. The book, ‘Paticcasamuppada: Practical Dependent Origination’ by Buddhadasa Bhikkhu (Bhikkhu meaning monk), will be referenced as an adjunct to the commentary for Thomas 7. Buddhadasa’s text illustrates an authentic way of understanding the primary teachings of the Buddha—at the centre we find the concept of ‘Paticcasamuppada’. In addition, the views of Stephen Batchelor, a former Buddhist monk and widely published author, will be mentioned as a reflection of the dynamism Buddhist beliefs have had and he suggests should continue to have in the modern world. Batchelor’s view on contemporary Buddhist communities reflects what 77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree illustrates—the necessity for critical analysis of Christian doctrine. Such a critique would see the fundamental truths of Yeshua’s teachings in the Gospel of Thomas come to life in our everyday lives. Moreover, Batchelor shows how humans desire the structure of institutions, which are built on dogma and formalised practices. This desire in people has altered the essential meaning of Paticcasamuppada, due to general apathy and a lack of critical analysis. For this reason, Batchelor’s views are also presented here to illustrate a parallel to the apathy we find in contemporary Christian orthodoxy. The desire for dogma and an institution that represents it demonstrates a weakness in humankind. There is a desire to make the messenger into the message, rather than listen to the message—perhaps because this takes more effort (we can see this in Thomas 13, 43, 52 and 88). It is this tendency that sees people worship Jesus and Buddha as deities, their image replacing their message.

Throughout 77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree, we see how the original teachings (sayings) of Jesus have been re-contextualised in the New Testament, through placing them within various narratives. The sayings in the Gospel of Thomas are reliable, because they are simply quotes. Indeed, this fits the scenario of an aural tradition, which would have initially been the only link to Jesus’ teachings. There is strong evidence for this pattern of distortion throughout human history. We can cite such evidence in the way the Buddha’s teaching of Paticcasamuppada was interpreted over time. This example is one that links and ratifies the words of Yeshua in Thomas 7. It also illustrates how the teachings of both men have been interpreted in different ways for various reasons.

In the commentary for Thomas 7, we see the revelation of the nature of the human—a beast, the flesh the soul inhabits. The baffling nature of this saying reflects the necessity for Jesus to conceal the true meaning of some of His teachings, as they did not fit the beliefs of His contemporaries. Indeed, Christian orthodoxy apologists argue that a typical rabbi of Jesus’ time would not utter such cryptic and sometimes blasphemous rhetoric. This is true. Jesus was not typical of His time, He was the new wine. The words of Thomas 7, ‘Lucky is the lion that the human will eat, so that the lion becomes human. And foul is the human that the lion will eat, and the lion still will become human,’ challenge the notion of humanity as a creation separate from the animals around them. This is what the Abrahamic religions maintain. They believe Human bodies were uniquely created apart from all other creation, then the soul was created for the flesh. We see in Thomas 29 that this is incorrect. However, as in other sayings, Thomas 7 is imbued with more than just this practical and logical wisdom. Thomas 7 describes the nature we tend to fall back into, the nature of the ignorant animal, which has no altruistic feelings—it places itself at the centre of everything and becomes angered and disturbed by events that are unfavourable to its cravings and desires. How then does this relate to the primary teachings of Gautama Buddha? If we look at the profoundly insightful teaching of Paticcasamuppada, we can see how it is closely linked to Thomas 7.

Sitting under a bodhi tree (a fig tree native to India), Gautama Buddha meditated, determined to find the path out of suffering. It was at this point he attained enlightenment. In real terms, this did not mean he began to glow with light and was able to perform fantastical feats. It meant that he had a deep inner peace, acquired through a profound understanding of the reality or truth (Dharma) we encounter in this existence. The enlightenment he attained gave us Paticcasamuppada or Dependent Origination. The version given here is from the text ‘Paticcasamuppada: Practical Dependent Origination’ by Buddhadasa Bhikkhu, (Published in 1992 by the Vuddhidhamma Fund, Distributed by Thammasapa)—this and other versions can be found online. The eleven conditions of Paticcasamuppada are given in various orders after Buddha’s enlightenment, but the two presented here are The Regular or Forward Order and the Extinction in the Middle. The latter is presented as further evidence for Buddhadasa’s assertion that Paticcasamuppada is experienced in a split second, rather than a whole lifetime.

The Regular or Forward Order:

‘Ignorance gives rise to mental concocting;

Mental concocting gives rise to consciousness;

Consciousness gives rise to mentality/materiality;

Mentality/materiality gives rise to the sense bases;

The sense bases give rise to contact;

Contact gives rise to feeling;

Feeling gives rise to craving;

Craving gives rise to attachment;

Attachment gives rise to becoming;

Becoming gives rise to birth;

Birth gives rise to old age and death.’

Buddhadasa explains that this is called one turning of the chain, or wheel, of Dependent Origination, from beginning to end. He also spends significant time clarifying the conventional, and he implies misguided understanding of what this process actually involves. In some Buddhist faiths, Paticcasamuppada is understood as the experience of one whole lifetime, which is on a continuous loop to become endless lifetimes if craving does not cease. Therefore, it becomes an accumulative result of behaviours within a lifetime, which then determines the condition in which one is reborn—the karma effect. Buddhadasa’s view is very different—it is this point of view we see linking to Thomas 7. Buddhadasa also explains that well-meaning disciples of the Buddha, who had expanded on the original Pali Canon, established some of the current, divergent, Buddhist beliefs.

Gautama Buddha chose to give his sermons in the Pali language, the native tongue of the common people. This observation is made by Buddhadasa and Stephen Batchelor, which will be explored further on. As with Christian beliefs and the Gospel of Thomas, Buddhist scholars now have access to the original Pali manuscripts, which contradict some of the beliefs within the various sects of Buddhism. Buddhadasa maintains that Gautama Buddha never spoke about the mechanism of rebirth—Batchelor also supports this. Rebirth was a mainstream ideology, the belief of the Indian culture Gautama Buddha was born into. The Buddha showed no interest in entering into a dialogue about the unknown. The questions of mind/body dualism, the mysteries of the universe, and reincarnation, were distractions to his path. He implied reincarnation’s position as an accepted eventuality, but did not attempt to explain the process. The process of the soul’s journey is described here, in 77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree, through the teachings of Yeshua in the Gospel of Thomas.

Buddhadasa asserts that Paticcasamuppada describes what humans go through in their everyday lives, in a split second of impassioned craving. To paraphrase Buddhadasa: the process of Paticcasamuppada (Dependent Origination) can be compared to a child who has a desirable toy placed within its presence. The child is symbolic of who we are when we are in a state of ignorance. In this state, we have no control over our thoughts and cravings. The toy represents any mental or material thing we might have, imagine, or desire. When the toy has been removed, or an obstacle is placed before it, our sense bases arise. This distraction makes contact with our eyes, ears, smell or touch, which then give rise to feelings of anger, loss, lust, disappointment, and so on. The attachment gives rise to the birth, which is the illusion of self or ego. ‘Old age and death’ represent the symbolic suffering within this cycle and the inevitability of this suffering arising again, due to ignorance. This process is comparable to Thomas 7. Ignorance is the rebirth of the primal animal—which is in us and is ‘the human that the lion will eat’ so that ‘the lion still will become human’—reborn with ignorance and craving. However, as in the first part of Thomas 7, if the lion (the physical manifestations we engage with every day) makes contact with the human (the person who consumes the lion), then the lion becomes human—the process has been profitable to the human. This human has engaged with the physical/material world and the process of Paticcasamuppada, becoming aware—no longer ignorant, no longer craving. The process is reversed in the Extinction in the Middle recitation of Paticcasamuppada. Here, the person is metaphorically eating the lion, because they have actively engaged with this life (Thomas 81, 110).

If we require more evidence that supports Buddhadasa’s position on the interpretation of Paticcasamuppada, we can look at another form;

The Extinction in the Middle.

‘Ignorance gives rise to mental concocting;

Mental concocting gives rise to consciousness;

Consciousness gives rise to mentality/materiality;

Mentality/materiality gives rise to the sense bases;

The sense bases give rise to contact;

Contact gives rise to feeling;

Feeling gives rise to craving;

Because of the extinguishment of craving, attachment is extinguished;

Because of the extinguishment of attachment, becoming is extinguished;

Because of the extinguishment of becoming, birth is extinguished;

Because of the extinguishment of birth, old age, death, sorrow, lamentation, etc are extinguished.’

In this example of Paticcasamuppada, the person becomes aware of the reasons for craving and is able to rationalise the true value of the thing causing the suffering. Even though Gautama Buddha was the enlightened one, he still went through the process of his body becoming old and expiring. It is how he saw this process, and how he accepted it, which makes the difference. The recitation of Paticcasamuppada, with the extinction in the middle, is the one the Buddha would have become adept at using in his everyday life. It is the main reason he was the first Buddha. Paticcasamuppada, Extinction in the Middle, is the evidence of this process being not of a lifetime, but of a split second. The root cause of suffering is the stealthy lion under the skin, the ignorant child within, which we can extinguish, because we know where and how this rebel will attack (Thomas 103).

In 77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree, there are references made to several texts and writers to illustrate various points. These references should not be seen as a particular preference toward one system of beliefs over another, nor as a critique of one system over another. The point has been made in other commentaries that all faiths have aspects of truth, because the Father/Source has been seeking us out. Some have heard its voice with clarity; for others the voice has been muffled by innate human weaknesses. Here, we can make the analogy of a huge, complicated jigsaw puzzle, which has been swept off a table. Pieces have been discovered and yet other pieces have been copied through a thick fog (human weakness and this realm). They appear to fit, but do not complete the original puzzle. When we stand back and look at the picture created, it becomes obvious that certain pieces stand out as having a different tone or texture. The texts that are referred to in the commentaries make some pieces of the puzzle more defined. They have been found to have clarity and authenticity, through their harmonious fit into the picture Jesus has described in the Gospel of Thomas. Batchelor’s views are used, in part, to enhance a point mentioned above. It is apparent in the lecture referenced that he had become disillusioned with the life of a monk, in both Tibetan and Zen Buddhism. This fact tends to colour his attitude toward the spiritual elements which have evolved in Buddhism. However, for the purposes of this commentary, we can see how some of his points are of relevance here.

To find the full transcript of Stephen Batchelor’s lecture search for ‘ABC Radio National, Batchelor, The Secular Dharma’.

Batchelor makes some strong points, which parallel those made for these commentaries. He points out that the Buddha’s teaching, about the impermanence of all things, has been a catalyst for the many varied applications of Buddhist practice in different places.

‘…if we look at this from a historical perspective, is that Buddhism has survived, and has flourished, precisely because it has the capacity to re-imagine itself, to re-think itself, to present itself in a different way, according to the needs of the particular people, the particular time, the culture, in which it finds itself at a given time. Buddhism is very fluid in this sense…each particular form of Buddhism that has come into being, has done so in its own peculiar way, which suits and is adapted to the particular situation of its historical background.’

The point Bachelor makes here is something the Christian orthodoxy needs to consider. Certainly, when we look at the history of Christian doctrine we see that it has developed in response to the context it came from. Constantine I facilitated the creation of the Nicene Creed to unify the Christian doctrine. At the time, various bishops had different positions on how Christianity should be established within society. Constantine wanted to have a central doctrine to stop the squabbling. One could argue that his background influenced the concept of a man seen as a living god, because of his experience with the Caesar legacy. All Caesars were responsible for ensuring the deities of their time were being worshipped appropriately. It was also not uncommon for Caesar to see himself as a god. This structure of authority, which was a pyramidal one, can be seen reflected in the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox hierarchy. It is also reflected in the Nicene Creed. The early part of the twenty-first century has seen much change; Christian Orthodoxy must change with it. What science has shown us indicates that we can no longer accept the juvenile beliefs about a Creator God. This is the legacy of Jesus’ teaching, which sounds contradictory, but is what we discover through the Gospel of Thomas. It may seem like an atheist manifesto, but by definition ‘atheist’ means someone who does not believe in a god or gods: In 77th Pearl: The Perpetual Tree we find that God is in all things, just as It is in Yeshua and in all of humanity. In this sense, our concept of god becomes a thing that connects all conscious beings.

To illustrate how people have desired something other or more than what the messenger is offering, we can look at some parallels in Buddhism. Batchelor makes some strong points about how people have always craved knowledge of things they cannot experience with their physical senses. They have wanted to know more than how to be happy in this life—they wanted to know what was next and what that looked like. Batchelor argues that the Buddha, according to the original Pali Canon, did not encourage this kind of thinking. He says:

‘And whenever the Buddha was presented with these kinds of questions, or asked these questions, he wouldn’t give an answer. All he would say was, “To explore such kinds of questions is not conducive to the path that I teach.” And the point is not to pursue these kinds of questions in the hope that Buddhism will answer them for us, but actually to simply not pursue them, and to recognise that what really is important, is not having a correct description of the state of affairs in reality. But what matters is doing something that might make a real difference in the quality of your life here and now.’

Batchelor also makes an interesting point about why institutions begin to offer solutions to problems. They desire to substantiate their position as a valid system of what they purport to represent. In Christian orthodoxy, these are the sacraments of birth, marriage, and death. Similarly, Batchelor describes how contemporary Buddhist orthodoxy has claimed a kind of technology to alleviate suffering. They offer a technique that presents itself as the answer, drawing-in people wanting this relief. Batchelor states:

‘…They like to present Buddhism as an effective technique for reducing suffering: “you’ve got a problem? OK, here’s a technique, it’s called meditation, and it’s very effective. You do it right, you’ll get rid of suffering.” That I think is, again, in reducing Buddhism to a technological strategy, a kind of a self-help process that has almost claims to have a kind of quasi-scientific reliability…I think you can master all the techniques of meditation and remain just as screwed up as you were before you started.’

The attitude Batchelor describes here is also reflected in the way Buddhist monks withdraw from conventional life—but this is not a sustainable practice for the majority. In Buddhadasa’s book, mentioned above, he suggests that one should avoid the enjoyment of nature and the simple pleasures of eating, because this encourages the process of craving. As Batchelor has suggested, such prescribed methods do not guarantee success. In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus asks that we engage with the world, not withdraw from it. Moreover, through the process of ‘motion and rest’ (Thomas 50), at the end of this journey, we ‘[become] passers-by’ (Thomas 42). In Thomas 7, we are asked to participate in (consume) the physical/material existence, so that we might grow and turn these experiences into the human—the living spirit, which is the fruit Jesus loves most. This is why, in Thomas 90, Yeshua tells us ‘[His] yoke…is gentle’.

In Stephen Batchelor’s book ‘Buddhism without Beliefs’ (published by G.P. Putnam’s and Son’s, 1997), he explains the way the Four Noble Truths should be perceived and practiced in our everyday lives. Batchelor stresses that Gautama Buddha did not intend these truths to be a kind of mantra (which become passive recitations). Rather, they should be metaphors for confronting the individual experience of suffering and for how to overcome these obstacles. They should not be used to console those who want a rebirth, which leads into wealth and prosperity. He also suggests that the Buddhist should be an active Agnostic—not desiring or denying the existence of a God (Ibid page 18-19). Batchelor asserts that because the Buddha Dharma has become part of a religion—imbued with dogma and discourse about the metaphysical—it has diverged from the purpose it was intended for. Here, there is a direct parallel with the way Jesus’ teachings had been absorbed into a culture of fear: Fear of a creator God and His pending wrath for humanity’s wickedness. Evidently, this was a wickedness that was not seeded and perpetuated by men themselves, but what became an adversary of God. This false perception sees Jesus turned into a vengeful deity in the Gospel of John (Revelations), rather than the wise avatar, all-forgiving man in the Gospel of Thomas and portions of the other gospels. This erroneous attitude reflects humanities inability to see their soul as an progeny of the Source, intimately connected to It.

If we consider that the soul does not die, though the flesh that houses it will, then our focus needs to be on nurturing the growth of the mind/spirit. When a person accepts the spiritual nature of all humans they consume the lion—that is, they interact with the physical world but they are not harmed or disturbed by it. The opposite is true if the person is enamoured of the physical world and denies the essence that is within. The life force that moves between all things will continue to pass through these bodies, but never truly live. Although the lion will manifest in human form, the essential soul becomes a victim of this world. Yeshua asks that we interact with the world; but first we should restrain it. Through the process of containing its impact on the mind we can benefit from what it has to offer. This enables growth from the experiences we encounter in this life, unharmed (Thomas 35 and 42).

________________________________________

The information you will find in this book is so important that the author has financed the creation of the eBook, for free download. However, he cannot afford to have printed copies made and delivered. If you wish to purchase a hard copy click on the link below.

Amazon ibook, kindle, paperback, hardcover